Why CT scanners matter

Computed Tomography (CT) scanners are among the most widely used medical imaging systems in diagnostic radiology because they are fast, detailed, and available in emergency rooms and clinics worldwide. From stroke triage to cancer staging and trauma work-ups, CT has become a cornerstone of modern medicine—delivering cross-sectional, 3D images that guide life-saving decisions every day.

Table of Contents

- What is a CT Scanner? (Definition & Overview)

- A Short History of CT

- How CT Works: The Imaging Principle

- Key Hardware Components

- Clinical Applications & Use Cases

- CT vs MRI, X-ray, and Ultrasound

- Safety & Radiation Dose: Risks and How They’re Minimized

- Maintenance & Technical Considerations (for Biomed/CE teams)

- Cost & Accessibility

- Future Innovations & Trends

- Simple Analogies to Demystify CT

- Final Summary

- References

What is a CT Scanner? (Definition & Overview)

A CT scanner is an X-ray–based diagnostic imaging device that rotates an X-ray source and detector array around the patient to acquire multiple projections, which a computer reconstructs into cross-sectional “slices” and 3D volumes. Compared with conventional radiography, CT separates overlapping structures and visualizes soft tissues, vessels, and bone with high spatial resolution and speed.

CT images are displayed in Hounsfield Units (HU)—a quantitative scale where water is ~0 HU, air is ~-1000 HU, and cortical bone is ~+1000 HU—helping radiologists distinguish tissues and materials (e.g., calcification vs. fat).

A Short History of CT

- 1960s–1970s: Godfrey Hounsfield (UK) and Allan Cormack (South Africa/USA) independently developed the mathematics and engineering that led to the first clinical CT in 1971–1972 (EMI Mark I). They received the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this breakthrough.

- 1990s: Slip-ring technology enabled continuous rotation and helical (spiral) CT, dramatically accelerating scanning and ushering in multi-detector CT (MDCT) for broader coverage per rotation.

- 2000s–2010s: Widespread adoption of MDCT, cardiac CT, CT angiography, and iterative reconstruction for lower dose.

- 2020s: Photon-counting CT (PCCT) enters clinical practice, promising higher spatial resolution, inherent spectral imaging, and potential dose/contrast savings.

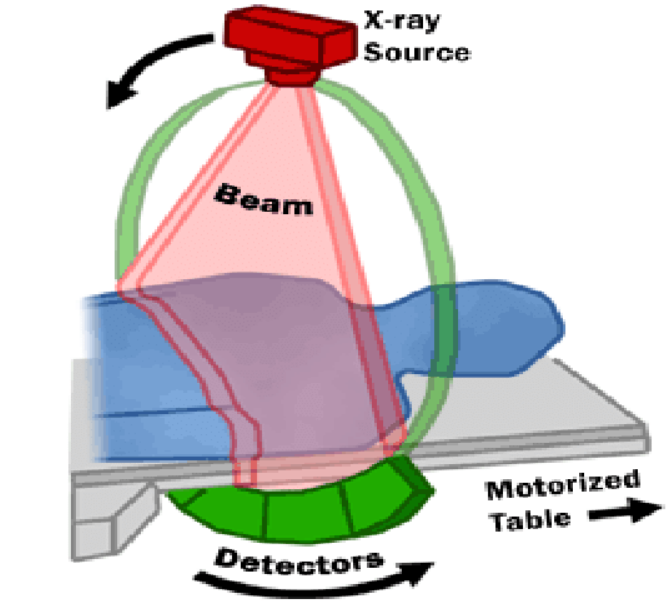

How CT Works: The Imaging Principle

- Data acquisition: As the gantry rotates, the X-ray tube emits fan or cone-shaped beams through the body; detectors measure the transmitted photons for many angles. With table motion (helical CT), a volume is covered rapidly.

- Reconstruction: The projection data (a “sinogram”) are converted into images by algorithms.

- The classic method is Filtered Back Projection (FBP).

- Modern systems use iterative reconstruction (IR) and model-based IR to reduce noise and artifacts at lower doses while preserving resolution.

- Quantification: Reconstructed voxel values are mapped to Hounsfield Units for standardized tissue characterization.

Analogy: Imagine shining a flashlight through a loaf of bread while rotating it and measuring how much light exits; a computer uses those measurements to rebuild every slice—revealing raisins (lesions), seeds (calcifications), and the shape of each slice.

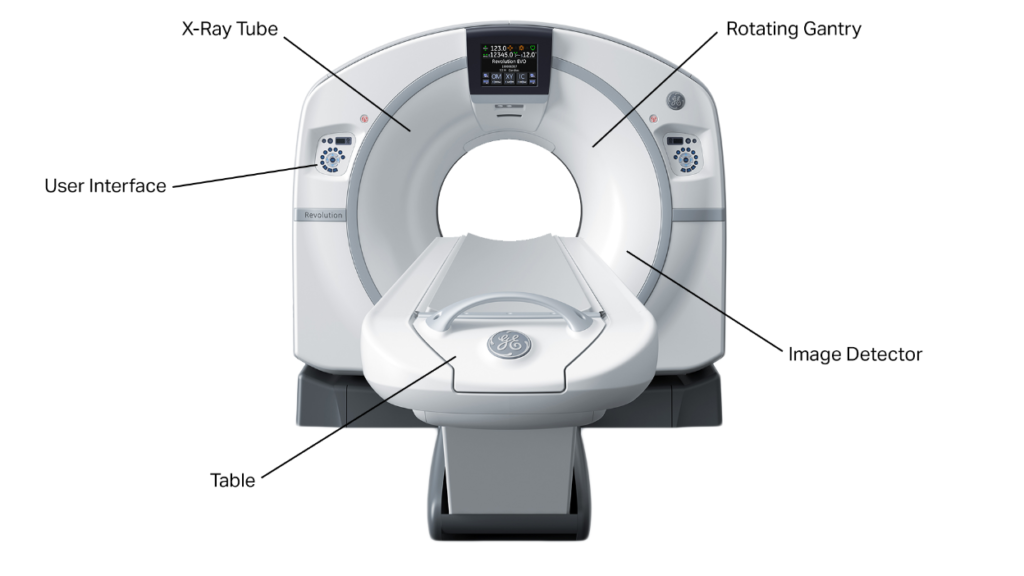

Key Hardware Components

- Gantry: A rigid rotating frame that houses the X-ray tube, detectors, collimators, and sometimes anti-scatter grids. Modern gantries rotate in ~0.25–0.35 s. Slip-rings provide power/data across the rotating/stationary interface for continuous spin.

- X-ray tube & generator: High-heat-capacity tubes (often >5–8 MHU) with adjustable kVp and mA; automatic tube current modulation (ATCM) tailors mA to patient size and anatomy to lower dose.

- Detector array: Scintillator-photodiode assemblies (e.g., gadolinium oxysulfide or ceramic) convert X-rays to electrical signals; in photon-counting CT, semiconductor detectors count individual photons and measure energy.

- Patient table (couch): Precisely indexed, carbon-fiber design minimizes artifacts and supports helical pitch accuracy for consistent geometry and dose.

- Computer system & reconstruction engine: High-performance CPUs/GPUs run FBP/IR algorithms; modern systems increasingly integrate AI-assisted reconstruction and automated dose monitoring.

Clinical Applications & Use Cases

- Emergency/Trauma: Rapid whole-body CT for polytrauma; head CT for suspected intracranial hemorrhage; CT angiography (CTA) for vascular injury.

- Stroke: Noncontrast head CT to exclude bleed; CTA/CT perfusion to plan thrombectomy.

- Chest: Pulmonary embolism (CTPA), pneumonia, interstitial lung disease, lung cancer staging and screening (low-dose CT).

- Abdomen/Pelvis: Appendicitis, urolithiasis, bowel obstruction, trauma solid-organ injury, oncologic staging.

- Cardiovascular: Coronary CTA, aortic disease, pre-TAVR planning.

- Interventional guidance: CT-guided biopsies, drainages, ablations—benefiting from precise needle trajectory and rapid confirmation scans.

Guideline frameworks such as the ACR Appropriateness Criteria help clinicians choose CT when it is the most suitable test for a given symptom complex.

CT vs MRI, X-ray, and Ultrasound

- Speed & availability: CT is typically faster and more available than MRI, particularly valuable in emergencies.

- Tissue contrast: MRI offers superior soft-tissue contrast (e.g., brain, ligaments), but CT excels at lung, bone, and calcifications, and provides high-quality angiography with iodinated contrast.

- Radiation: CT uses ionizing radiation; ultrasound and MRI do not. Risk-benefit assessment and dose optimization are therefore critical for CT.

- Artifacts/contraindications: CT is less sensitive to motion than MRI and is compatible with most implants; ultrasound is portable and inexpensive but operator-dependent and limited by gas/bone.

Safety & Radiation Dose: Risks and How They’re Minimized

Dose metrics you’ll see on the console

- CTDIvol and DLP are standardized output metrics reported by the scanner; patient-specific absorbed doses vary with size and anatomy. SSDE (Size-Specific Dose Estimate) refines dose estimation using patient size.

Risk context

- For medically indicated exams, benefits typically outweigh risks. However, unnecessary imaging should be avoided, especially in children who are more radiosensitive.

- A 2025 modeling study estimated that current U.S. CT utilization could contribute to ~100,000 future cancers annually if present practice patterns persist—highlighting the importance of justification and optimization rather than a reason to avoid indicated scans. (Modeling study; risk to any single patient from one scan is small.)

How dose is reduced in practice

- Justification & ALARA: Scan only when appropriate; use Diagnostic Reference Levels (DRLs) and the ALARA principle per ICRP/IAEA guidance.

- Protocol optimization: Tailor kVp/mA, pitch, and collimation; employ automatic tube current modulation, iterative reconstruction, and patient centering.

- Pediatric strategies: Adjust technique to size, restrict multiphase studies, and leverage campaigns like Image Gently.

Typical dose ranges (effective dose; approximate and protocol-dependent):

Head CT ~2 mSv; Chest CT ~7 mSv; Abdomen/Pelvis CT ~8–10 mSv. (Values vary by body size, scanner, and protocol.)

Maintenance & Technical Considerations (for Biomed/CE teams)

- Daily/weekly QC: Image uniformity, CT number accuracy (water ~0 HU), artifact checks, laser alignment, and dose index verification. Programs align with the ACR CT Accreditation QC manual and local regulations.

- Acceptance/annual testing: Comprehensive testing after installation or major service (e.g., CTDI phantom, slice thickness, spatial resolution, low-contrast detectability), following AAPM guidance.

- Regulatory safety: Conformance to IEC 60601-2-44 (basic safety and essential performance for CT) and national radiation-protection rules; maintain dose-tracking archives (e.g., DICOM RDSR).

- Lifecycle & uptime: Track X-ray tube heat units and use logs to anticipate tube replacements; keep spares for table drive, HV cables, and cooling. Iterative reconstruction and detector calibration updates should follow OEM/AAPM change-control practices.

Cost & Accessibility

Accessibility: CT availability and use vary globally. OECD indicators track CT scanners per million population and CT exams per 1,000 inhabitants, showing wide cross-country differences and growth in utilization over the last decade.

Cost elements to plan for

- Capital purchase (scanner + options), site prep (room build-out, shielding, HVAC), installation, service contracts, tube replacements, and tech staff training. Noncapital costs (contrast media, power, IT integration) impact total cost of ownership. (Planning frameworks from ECRI and ACR/AAPM are commonly used.)

Indicative price ranges (context, not universal):

- Industry and nonprofit sources report that new multi-slice CT systems span roughly hundreds of thousands to >$1.5–2.2M, with spectral/dual-energy and high-end systems at the upper end; refurbished units can be substantially less. Service contracts for mid-range systems are often in the tens of thousands of USD per year, depending on coverage. (Exact prices vary by region, features, and purchasing agreements.)

Note: For procurement in public systems, consult local tenders, HTA reports, and standardized equipment planning guides to obtain region-specific figures.

Future Innovations & Trends

- Photon-counting CT (PCCT): Energy-resolving detectors deliver higher spatial resolution, intrinsic spectral imaging, and potential dose/iodine savings; first FDA-cleared clinical PCCT entered U.S. practice in 2021.

- Deep learning reconstruction (DLR): AI-based reconstruction suppresses noise and reduces artifacts at lower dose while preserving texture—now moving from research to routine.

- Dual-energy/spectral CT: Material decomposition (e.g., uric acid vs. calcium, iodine maps) improves lesion conspicuity and quantitative imaging.

- Dose intelligence & protocol management: Enterprise systems (per AAPM Report 233) standardize protocols, audit dose, and reduce variability across fleets.

- Workflow & access: Low-footprint and bedside CT for ICU/ED, plus expanding population screening (e.g., lung) with optimized low-dose protocols.

Simple Analogies to Demystify CT

- Slices of bread: A CT slice is like a bread slice—many slices stack to make a 3D loaf.

- Sun and shadows: As the “sun” (X-ray tube) circles, different shadows (projections) are captured; reconstruction turns shadows into a picture.

- Temperature scale: Hounsfield Units are like degrees on a thermometer—standard numbers let you compare images across scanners and time.

- Adaptive headlights: Automatic tube current modulation is like car headlights that brighten on a dark road and dim in daylight—just enough light (X-rays) for the view you need.

Final Summary

- CT scanners use rotating X-rays and detectors to create cross-sectional, quantitative images fast.

- Modern CT relies on helical acquisition and iterative (now AI-assisted) reconstruction to keep dose low and image quality high.

- Clinical reach spans emergency, oncology, cardiovascular, and image-guided procedures; appropriateness criteria guide when to choose CT.

- Safety hinges on justification, optimization, and QC (CTDIvol/DLP/SSDE, DRLs, pediatric adjustments), with benefits outweighing risks when scans are indicated.

- Costs depend on features and service; accessibility differs globally, tracked by OECD.

- Trends: photon-counting CT, deep-learning reconstruction, and enterprise protocol management are shaping the next decade.

References

- National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB). Computed Tomography (CT). INIBI

- StatPearls. Computed Tomography (CT). (NCBI Bookshelf). NCBI

- The Nobel Prize (1979). The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine – Hounsfield & Cormack. NobelPrize.org+1

- Flohr et al. Computed Tomography: Physical Principles and Recent Technical Developments. (overview of slip-ring/helical/MDCT). ScienceDirect

- Image Wisely / ACR–RSNA. CT Dose Optimization & Iterative Reconstruction. PubMed

- FDA. What Are CTDIvol and DLP? and Medical X-ray Imaging – CT Safety. U.S. Food and Drug AdministrationEndovascular Today

- AAPM Report TG-204. Size-Specific Dose Estimates (SSDE) in Adult Body CT (and AAPM CT report library). AAPM+1

- National Cancer Institute (NCI). Radiation Risks and Pediatric CT. Institut National du Cancer

- Smith-Bindman et al., JAMA Internal Medicine (2025) & NIH Research Matters summary; ACR statement on the study. JAMA NetworkNational Institutes of Health (NIH)Accreditation Support

- IEC 60601-2-44. Particular requirements for CT equipment. (standard overview). Glassbeam Inc.

- ACR CT Accreditation. Quality Control Manual / Phantom Testing. Image Wisely

- AAPM Report 233. CT Protocol Management and Review. PubMed

- Mettler et al. Effective Doses in Radiology and Diagnostic Nuclear Medicine: A Catalog. Radiology (2008). ACR Search

- ACR Appropriateness Criteria (modality selection & relative radiation levels). PMCNICE

- OECD. CT scanners per million & CT exams per 1,000 inhabitants; Health at a Glance 2023. OECD+2OECD+2

- ECRI (capital planning; spectral CT cost context) & industry service-cost guides (Block Imaging). ECRI and ISMPECRI and ISMPblockimaging.com

- Radiology / RSNA & regulatory notes on photon-counting CT (clinical reviews; FDA clearance of Naeotom Alpha). IEC WebstoreSiemens Healthineers

- Wang et al., npj Digital Medicine (2020). Deep learning–based CT image reconstruction: a review. AAPM

- Review of X-ray/CT detector technology and materials