Mammography: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Engineers and Healthcare Professionals

Introduction

Breast cancer remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths among women worldwide. Mammography, a specialized low-dose X-ray imaging technique, plays a critical role in early detection and diagnosis of breast abnormalities. For healthcare professionals and biomedical engineers, understanding how mammography works—its principles, technology, safety considerations, and future innovations—is essential for improving patient outcomes and advancing medical imaging systems.

Table of content:

What is a mammography

A Short History

How it Works: The Imaging Principle

Key Hardware Components

Clinical Applications & Use Cases

mammography vs other radiology imaging devices

Safety & Radiation Dose: Risks and How They’re Minimized

Maintenance & Technical Considerations (for Biomed/CE teams)

Cost & Accessibility

Future Innovations & Trends

Simple Analogies to Demystify mammography

Final Summary

References

What is Mammography?

Mammography is a diagnostic imaging method that uses low-energy X-rays to produce detailed breast images. It is considered the gold standard for breast cancer screening because it can detect tumors and microcalcifications before they become clinically palpable. This early detection significantly improves survival rates and treatment success.

A Brief History of Mammography

1913: Albert Salomon first studied breast tissue with radiography, showing the potential of X-rays in cancer detection.

1960s: Dedicated mammography units emerged, replacing general-purpose X-ray machines.

2000s: Digital mammography replaced film-screen systems, enabling better image storage, processing, and lower doses.

Today: Advanced techniques like Digital Breast Tomosynthesis (DBT, or 3D mammography) and Contrast-Enhanced Mammography are standard in modern hospitals.

How Mammography Works: The Imaging Principle

Mammography uses low-energy X-rays (typically 25–32 kVp) to maximize soft tissue contrast.

The breast is compressed between two plates to reduce tissue thickness, lower scatter, and improve image sharpness.

Detectors (film-screen, CR, or digital flat-panel) record the transmitted X-rays to create a high-resolution image.

Analogy: Think of shining a flashlight through a thick book. If the pages are pressed together tightly, it’s easier to see differences between them — that’s exactly what compression achieves in mammography.

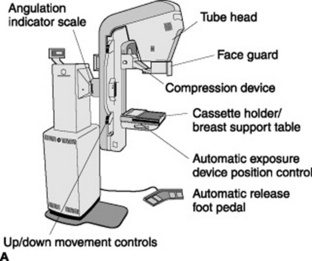

Key Components of Mammography Systems

Modern mammography units consist of:

- X-ray tube – Generates optimized low-energy photons.

- Compression paddle – Flattens the breast to improve image quality and reduce radiation dose.

- Detectors – Either digital flat-panel detectors or film-based systems.

- Gantry/Stand — allows positioning in craniocaudal (CC) and mediolateral oblique (MLO) views.

- Positioning supports – Ensure patient stability and reproducibility during imaging.

Clinical Applications & Use Cases

- Screening Mammography: Routine exams in asymptomatic women (ages 40–74, depending on guidelines).

- Diagnostic Mammography: For patients with lumps, symptoms, or abnormal screening results.

- Tomosynthesis (3D Mammography): Improves lesion detection in dense breasts.

- Contrast-Enhanced Mammography: Highlights vascularized lesions similar to MRI but at lower cost.

Mammography vs. Other Imaging Modalities

| Modality | Principle | Main Use | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mammography | Low-dose X-ray attenuation | Breast cancer screening | High resolution; proven tool | Radiation exposure; less effective in dense breasts |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance | High-risk patients, staging | Excellent soft tissue detail; no radiation | Expensive, time-consuming |

| Ultrasound | Sound wave reflection | Adjunct tool, cyst vs solid | Real-time, no radiation | Operator-dependent; lower resolution |

| CT | Cross-sectional X-rays | Rare in breast imaging | 3D anatomy | High radiation dose; not standard |

Safety and Radiation Dose: Risks and How They’re Minimized

Average dose per exam: ~0.4 mSv (comparable to 7 weeks of natural background radiation).

Risks: Small radiation-induced cancer risk, outweighed by the benefit of early detection.

Dose minimization strategies:

Use of ACR and MQSA standards for quality assurance.

Breast compression

Digital detectors (higher efficiency)

Automatic exposure control

Technical Considerations for Biomedical Engineers

Biomedical and clinical engineering teams are vital in ensuring mammography system performance by:

- Calibration & QC: Regular phantom imaging for contrast, resolution, and dose checks.

- Detector care: Digital detectors require flat-field calibration.

- X-ray tube lifespan: Must be monitored for heat load and performance.

- Compression paddle: Needs inspection for cracks, uniform pressure, and patient comfort.

- Regulatory compliance: Must meet FDA/MQSA or equivalent standards in each country.

Cost and Accessibility

Conventional Digital Mammography: $150,000–$300,000.

Digital Breast Tomosynthesis (DBT): $300,000–$500,000.

Operating costs: service contracts, detector replacement, ACR accreditation fees.

Accessibility: Limited in low-income regions; mobile mammography units are emerging as a solution.

Future Trends in Mammography

Innovations shaping the future of breast imaging include:

- Digital Breast Tomosynthesis (DBT) – 3D mammography reducing tissue overlap.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) – Advanced CAD systems for enhanced detection and risk assessment.

- Contrast-Enhanced Mammography – Better tumor characterization with contrast agents.

- Portable and Tele-Mammography – Expanding screening access in underserved regions.

- Photon-Counting Detectors: Improved contrast and lower dose (early adoption).

- Molecular Breast Imaging (MBI) and Dedicated Breast CT under evaluation.

- Patient-Centered Design: Less painful compression systems being developed.

Simple Analogy

Breast Compression: Like pressing pages of a book together to read fine print.

Digital vs Film: Like switching from printed photographs to digital photography — easier storage, processing, and sharing.

Tomosynthesis: Like flipping through the pages of a 3D photo album instead of staring at a single flat image.

Conclusion

Mammography is a cornerstone of breast cancer detection and management, blending precision imaging with advanced engineering. Its journey from early X-ray experiments to digital, AI-assisted systems has saved millions of lives worldwide. For biomedical engineers and healthcare professionals, understanding mammography’s principles, safety measures, and future potential is essential in advancing both technology and patient care.

References

- History of Mammography: Analysis of Breast Imaging Diagnostic Achievements over the Last Century. PMC, 2023.

- Breast Imaging Physics in Mammography. MDPI, 2023.

- Quality Assurance in Mammography: An Overview. PMC, 2023.

- Mammography: EUSOBI Recommendations for Women’s Information. PMC, 2011.

- Mammography as a Method for Diagnosing Breast Cancer. Radiol Bras, 2016.

- American College of Radiology (ACR). Mammography Quality Standards Act (MQSA).

- National Cancer Institute (NCI). Breast Cancer Screening with Mammography.

- Sechopoulos I. A review of breast tomosynthesis. Part I. The image acquisition process. Med Phys. 2013.

- Hendrick RE. Radiation doses and cancer risks from breast imaging studies. Radiology. 2010.

- Philips, GE, Siemens, Hologic – Manufacturer technical brochures (digital mammography and DBT).