Ultrasound Machines: Physics, Engineering Components, Clinical Applications, and the Future of Diagnostic Sonography

Table of Contents

- Introduction — The enduring importance of ultrasound in modern medicine

- What is an Ultrasound Machine? — Overview and definition

- A Short History of Ultrasound Imaging

- How Ultrasound Works — The Physical and Imaging Principle

- Core Hardware Components

- Transducer (Probe) types and piezoelectric technology

- Beamformer and signal processing chain

- Display and user interface

- Power, cooling, and control systems

- Imaging Modes and Applications

- B-mode, M-mode, Doppler, Color flow, 3D/4D, Elastography, Fusion imaging

- Clinical Applications and Use Cases

- Safety and Acoustic Output Indices

- Maintenance and Quality Control (for Biomedical Engineers)

- Cost and Accessibility Aspects

- Future Innovations and Research Directions

- Simple Analogies to Clarify Key Concepts

- Final Summary — Key Takeaways

- References

1. Introduction — The enduring importance of ultrasound

Among all medical imaging modalities, ultrasound (US) stands out for its real-time imaging, non-ionizing nature, and portability. From obstetrics and cardiology to emergency medicine, it is one of the most widely used diagnostic tools worldwide. Unlike CT or MRI, which require large, costly installations, ultrasound offers point-of-care imaging that can be deployed even in remote clinics.

Biomedical engineers, radiologists, and sonographers must understand not only how ultrasound produces images but also how its acoustic physics, hardware design, and signal processing affect clinical outcomes.

Keywords: ultrasound, diagnostic sonography, Doppler, echocardiography, medical imaging, biomedical engineering

2. What is an Ultrasound Machine?

An ultrasound machine is a diagnostic imaging system that uses high-frequency sound waves (2–15 MHz) to create visual images of internal body structures. It detects differences in acoustic impedance between tissues and converts reflected echoes into real-time grayscale images.

Core uses:

- Visualizing soft tissues, organs, vessels, and fetuses

- Assessing blood flow (via Doppler)

- Guiding interventional procedures

- Measuring organ dimensions and pathology

3. A Short History of Ultrasound Imaging

Ultrasound technology originated from SONAR (Sound Navigation and Ranging) developed during World War II.

- 1940s–1950s: First clinical applications in brain and abdominal imaging.

- 1960s: Development of real-time B-mode scanning.

- 1980s: Introduction of Doppler and color flow imaging.

- 1990s–2000s: 3D/4D imaging and digital beamforming revolutionized resolution.

- 2010s–Present: Portable, handheld, and AI-enhanced ultrasound became standard.

Today, ultrasound is indispensable in emergency rooms, ICUs, cardiology labs, and even field medicine.

4. How Ultrasound Works — The Physical and Imaging Principle

Ultrasound imaging relies on the piezoelectric effect:

Certain crystals (e.g., PZT — lead zirconate titanate) deform when voltage is applied, emitting high-frequency sound waves. When echoes return, these same crystals generate voltage proportional to the reflected signal intensity.

Basic process:

- Transmission: The transducer sends pulses of sound waves into tissue.

- Reflection & scattering: Echoes return when sound encounters interfaces of different acoustic impedances (e.g., soft tissue vs bone).

- Reception: The transducer receives echoes and converts them to electrical signals.

- Processing: Beamforming, envelope detection, and image reconstruction occur in milliseconds.

- Display: The processed signal appears as a grayscale (B-mode) or color-coded flow image.

The speed of sound in tissue (~1540 m/s) allows accurate distance calculation:Depth=(speed×time)2\text{Depth} = \frac{(speed \times time)}{2}Depth=2(speed×time)

Simplified analogy:

Think of the transducer like a camera flash — it sends out a short burst of energy, and the returning echoes form the “image,” except here the light is replaced by sound.

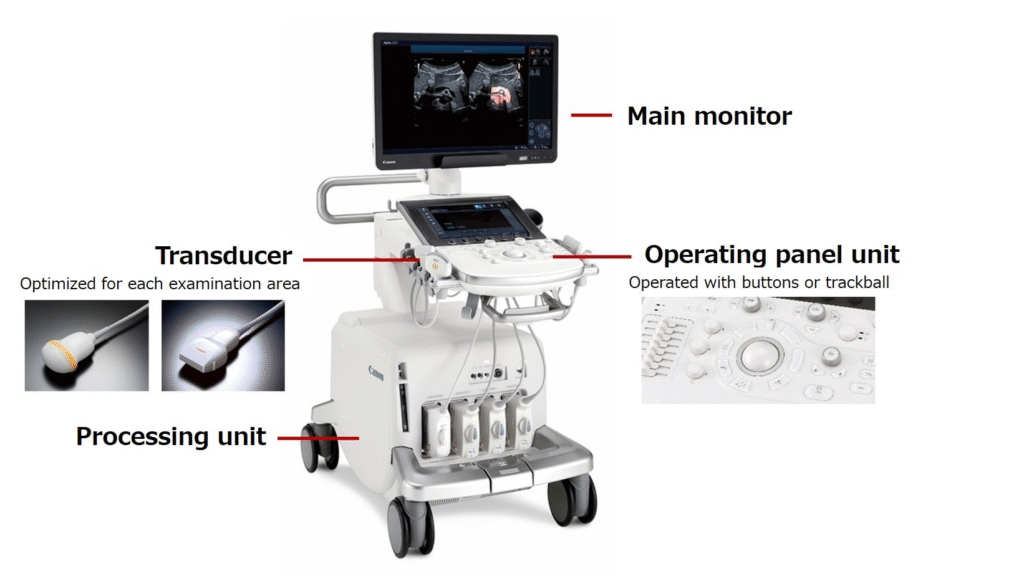

5. Core Hardware Components

a. Transducer (Probe)

The transducer is both transmitter and receiver.

- Piezoelectric crystals generate and detect ultrasound pulses.

- Matching layer improves impedance transfer to the body.

- Backing material absorbs unwanted vibrations for short pulses.

- Acoustic lens focuses the beam.

Types of probes:

- Linear array (5–15 MHz): vascular, musculoskeletal, superficial structures.

- Curvilinear/Convex (2–5 MHz): abdominal, obstetric.

- Phased array (1–5 MHz): cardiac (small footprint for rib gaps).

- Endocavitary: transvaginal or transrectal imaging.

- 3D/4D probes: electronically steered for volumetric imaging.

b. Beamformer and Signal Processing Chain

The beamformer controls timing (phasing) and amplitude of pulses across multiple elements to steer and focus the beam. It’s the heart of the ultrasound’s image formation.

Modern systems employ digital beamforming, enabling precise focusing, synthetic aperture imaging, and noise reduction.

Signal processing stages include:

- Time-gain compensation (TGC)

- Filtering and envelope detection

- Log compression for dynamic range adjustment

- Scan conversion to display (rectangular → polar coordinates)

c. Display and User Interface

Modern ultrasound systems feature high-definition LCDs, touch controls, and customizable workflow layouts.

Some include AI-based auto measurements (EF, fetal biometry, carotid IMT).

d. Power, Cooling, and Control Systems

Power modules deliver stable, filtered DC to high-frequency transducer circuits. Active cooling (fans or liquid systems) ensures stability for long scans. Biomedical engineers check isolation, leakage currents, and grounding regularly.

6. Imaging Modes and Applications

- A-mode (Amplitude): 1D echo amplitude plot — used in ophthalmology.

- B-mode (Brightness): 2D grayscale image — the standard diagnostic mode.

- M-mode (Motion): time-motion tracing — common in echocardiography.

- Doppler: measures blood flow velocity and direction.

- Color Doppler: maps flow color-coded on B-mode image.

- Power Doppler: more sensitive to low-velocity flow.

- 3D/4D Imaging: real-time volumetric imaging in obstetrics and cardiology.

- Elastography: measures tissue stiffness — valuable in liver fibrosis and oncology.

- Fusion Imaging: combines ultrasound with CT/MRI data for precise interventions.

7. Clinical Applications and Use Cases

- Obstetrics & Gynecology: fetal biometry, anomaly detection, amniotic volume.

- Cardiology (Echocardiography): LV function, valve assessment, hemodynamics.

- Abdominal: liver, kidneys, gallbladder, pancreas, spleen.

- Vascular: carotid, DVT, arterial stenosis evaluation.

- Musculoskeletal: tendons, ligaments, joints, guided injections.

- Emergency / Point-of-Care (POCUS): trauma, pneumothorax, cardiac arrest evaluation.

- Urology and prostate imaging (endocavitary probes).

- Breast imaging: complementary to mammography.

8. Safety and Acoustic Output Indices

Ultrasound uses non-ionizing radiation, making it one of the safest imaging tools. However, engineers and clinicians monitor two key safety indices:

- Mechanical Index (MI): related to cavitation potential.

- Thermal Index (TI): estimates tissue heating.

Regulatory guidance (FDA, AIUM):

- Keep MI < 1.9

- Keep TI < 1.5 for obstetric imaging

- Always apply ALARA (As Low As Reasonably Achievable) principle.

Proper training and awareness of acoustic exposure ensure patient and operator safety.

9. Maintenance and Quality Control

Biomedical engineers play a vital role in ensuring consistent performance:

Daily / Monthly QC:

- Visual inspection of probes and cables.

- Phantom testing (uniformity, depth calibration, resolution).

- Check grayscale and Doppler sensitivity.

Preventive maintenance:

- Clean probes with approved disinfectants only.

- Avoid cable bending and connector stress.

- Check fan filters and power grounding.

- Verify software calibration and updates.

Acceptance testing:

- Measure lateral and axial resolution.

- Verify maximum penetration depth and focal accuracy.

- Assess Doppler frequency accuracy (flow phantom).

10. Cost and Accessibility Aspects

Approximate cost ranges (as of 2025):

- Cart-based premium system: $70,000–$200,000

- Mid-range system: $30,000–$60,000

- Portable/handheld systems: $3,000–$15,000

Accessibility is expanding dramatically due to wireless handheld ultrasound (e.g., Butterfly, Clarius, Philips Lumify), connecting via smartphones/tablets and supported by AI-assisted image analysis — ideal for remote or emergency settings.

11. Future Innovations and Research Directions

- AI-assisted scanning: automated image acquisition and pathology detection.

- Deep learning beamforming: replacing traditional delay-and-sum with AI-enhanced reconstruction.

- Ultrafast ultrasound (thousands of frames per second): enabling functional imaging and shear-wave elastography.

- Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS): microbubble contrast for perfusion and oncology.

- Wireless and cloud-connected devices: integrated tele-ultrasound and remote diagnostics.

- Hybrid and fusion imaging: merging ultrasound with CT/MRI for guided therapy.

12. Simple Analogies to Clarify Key Concepts

- Ultrasound waves behave like bats’ echolocation — short pulses bounce off targets and return to form an echo-based map.

- The transducer acts like both a loudspeaker and a microphone, sending and receiving sound.

- Beamforming is like focusing a flashlight — multiple sources synchronized to illuminate one precise region.

13. Final Summary — Key Takeaways

- Ultrasound is a real-time, portable, non-ionizing imaging modality essential in nearly all clinical specialties.

- It works via the piezoelectric effect and relies on advanced signal processing and beamforming.

- Biomedical engineers ensure system accuracy via routine QC, phantom testing, and preventive maintenance.

- Safety indices (MI, TI) guide exposure control.

- The future of sonography lies in AI, ultrafast imaging, and wireless smart probes, transforming how imaging is delivered globally.

14. References

- Hoskins PR, Martin K, Thrush A. Diagnostic Ultrasound: Physics and Equipment, 3rd Ed. CRC Press, 2020.

- Kremkau FW. Diagnostic Ultrasound: Principles and Instruments, 10th Ed. Elsevier, 2022.

- American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM) Safety Statements.

- FDA: Information for Manufacturers Seeking Marketing Clearance of Diagnostic Ultrasound Systems and Transducers, 2019.

- Szabo TL. Diagnostic Ultrasound Imaging: Inside Out, 3rd Ed., Academic Press, 2014.

- WHO. Manual on Diagnostic Ultrasound Equipment Maintenance and Safety, 2021.